Harold Hilton: Modern Golf (1913)

BOOK REVIEW

MODERN GOLF by Harold H. Hilton

Outing Publishing Company, 1913

by Robert A. Birman

I recently read Harold H. Hilton’s 1913 book, Modern Golf, and was enlightened and entertained with every passing chapter. Hilton was winner of the British Amateur three times at the turn of the 20th century (1900, 1901 and 1911), once winner of the American Amateur Championship and a two-time British Open champion in 1892 and 1897.

I found myself midstream with three period pieces over the holidays this year; Harry Vardon’s The Complete Golfer, Horace Hutchinson’s Fifty Years of Golf, and Hilton’s so-called Modern Golf. I found myself putting down Vardon to finish both Hilton and Hutchinson; it simply was less engaging and ever more a tutorial with exponentially less color and flair. [A quick note about Fifty Years of Golf (which I strongly recommend). It is a collection of “reminiscences” by the great player, including some fascinating insights into the earliest days of Westward Ho! and eventual work to establish golf on the American East Coast in the 1880s. I believe many of the short excerpts which comprise the chapters were included over five decades in the famed periodical, Golf Illustrated, and were assembled for this one volume collection – all worth revisiting and enjoying today.]

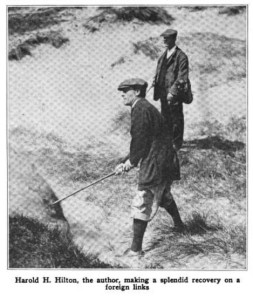

Hilton’s book seems to me to be the most personal and instructional, covering less common topics including long vs. short golf shafts, approach shots to winter greens, the mental game, and even a final chapter on the clothes for the game. Mr. Hilton concurs with Mr. Vardon in starting his manuscript with a chapter on the essential value of proper practice. While Vardon extolled a strict and methodical approach to training young players, Hilton subscribed to the value of simply putting in the time and learning one’s own abilities to shape shots and control trajectory with the incorporation of half and three-quarter shots, stating emphatically that he “served a long apprenticeship in the art of learning how to control the club in the upward swing.”

Hilton’s book seems to me to be the most personal and instructional, covering less common topics including long vs. short golf shafts, approach shots to winter greens, the mental game, and even a final chapter on the clothes for the game. Mr. Hilton concurs with Mr. Vardon in starting his manuscript with a chapter on the essential value of proper practice. While Vardon extolled a strict and methodical approach to training young players, Hilton subscribed to the value of simply putting in the time and learning one’s own abilities to shape shots and control trajectory with the incorporation of half and three-quarter shots, stating emphatically that he “served a long apprenticeship in the art of learning how to control the club in the upward swing.”

He placed a premium on iron play and practice with iron clubs vs. wooden clubs, as – in his view – that is where the difference resides in any tight match. He advocated practicing approach shots with a “straight faced club,” in order to sincerely learn how spin (even limited spin) is practically applied to a ball. What is clear is that, in that era, “practicing” meant slugging a few dozen balls to a quiet corner of a golf course and creating an engaging self-improvement session of one’s own. I can only imagine that these were some of the most precious hours of Mr. Hilton’s lifetime.

The mental aspects of the game in the early 1900s bear a striking resemblance to those even today. Not getting ahead of one’s self, staying in the moment, playing one shot at a time – these were all concepts explicated by Hilton, replete with ample admissions of his own shortcomings in pivotal moments. Like gurus of today, Hilton states clearly, “I do believe that it is possible to develop the habit of concentration.” Modern-era players might think of this as the commitment to a pre-shot routine. There are many comparisons throughout the book of American vs. British amateur players, and in this regard, Hilton felt Americans had a clear advantage. Walter Travis and Jerome Travers are cited, along with British sportsman, John Ball, as being best in their class. Qualities of “equability and equanimity” of temperament, then as now, were sought. Hilton’s accounts of squandering large leads due to indiscipline and a wandering mind support his thesis.

“I have noticed that the majority of good match players are inclined to be very silent men, and in consequence it is safe to assume that the lack of conversation is a virtue in the playing of the game of golf, and the class of conversation which should be particularly avoided is that species of running conversations with friends and acquaintances who happen to be among the spectators. Learn to bear your ill fortune without appealing for sympathy, as sympathy extended to a man during the course of play is more apt to upset him temperamentally than to strengthen his purpose in any way. The most reliable of golfers always prove to be those who play the game from beginning to the end of it without allowing any outside influence to affect them in any way whatever. To some golfers it is a difficult procedure to follow out, but it is truly wonderful how a young player can strengthen his temperament by continuous schooling.”

The big invention in Hilton’s prime was the creation of the bulger (driver). The convex face, as we know today, alleviates many minor faults. There is talk about filing of club heads and of learning the art to hitting a ball very hard; something that prior to the invention of the bulger was not often thought of as a premium. As Hilton so artfully puts it, “the game of golf twenty-five to forty years ago was more a game of scientific persuasion than sheer force; nowadays it is the scientific application of force, and for this change the alteration in the shape and balance of the club head due to the introduction of the bulger is almost altogether responsible.”

I liked Hilton’s depiction of the pros and cons of the introduction of the Carruther’s method of affixing club heads to shafts vs. the traditional method of using glue and pin. He remained in favor, most of all, of the scared method, believing that it allowed for infinite nuance in adjusting the lie angle of a club to accommodate the body characteristics of any golfer (by altering the angle of the scared joint with a shaft, the fitter (or professional) can change the lie angle of the club). Of course, socket clubs resulted in far less alteration of lie angle, which Hilton felt hampered the average player’s potential to experience promising results.

There is an extended section about imparting spin to the ball. Modern players need only conjure the manner of Zach Johnson to understand the approach that Hilton felt possessed the greatest control. This, and the infamous Vardon “push shot” (today known as a punch shot or knock-down shot) is covered at good length.

While reading Hilton’s advice from 1913, I was reminded of the first decade in which I read golf magazines as a youngster. Like Wee Nip readers everywhere, I found that nearly every major publication recycled 15-16 basic concepts each and every year. In 1913, Hilton bemoaned the truth that nearly every amateur over estimates the length of their clubs and, subsequently, is rarely beyond the hole on their approach shots. “The man who will make up his mind to play his approaches for a position past the hole, when the conditions of ground are heavy, will of a surety win a very large percentage of his matches. Not that he will of necessity be often past the hole, but for the reason that he will less seldom be ludicrously short of the green.” We read this even today with regularity.

The final chapter on golfing attire is a stitch. “One cannot ignore the fact that there still lurks in the minds of the golfing public a certain degree of prejudice against what I once heard a disgusted old time golfer term “The half naked stage.” The British players wore jackets. The Americans, sweaters. The horror! Hilton recounts Chick Evans’ honorable gesture in 1911 to complete a tournament in Britain in uncommonly high heat with a heavy tweed jacket. It hampered Evans to no end yet the general public appreciated the courtesy. Suspenders (braces) vs. belts? It’s covered. Knickerbockers vs. slacks? Also in there. While impossible to imagine, Hilton felt that, “[when] I commence to get down to play the shot, they [slacks] draw tightly across the knee and I am conscious all the while of the fact that they are thus drawn and it is a most uncomfortable feeling. When the professional first began to emancipate himself from the time honored custom of wearing long trousers and turned out in knickerbockers just like his amateur brothers, the first members of the fraternity who had the temerity to break away from traditional usage, he had to put up with a goodly degree of caustic comment, but they were wise in their generation, and from a utilitarian point of view knickerbockers are, to my way of thinking, by far the most comfortable form of nether garment in which to pursue the game of golf.”

There are countless books on golf now out of copyright and easily accessible for Kindle, iPad or e-readers. It is a thrill to delve deeper into the world of our sport from those who shaped it. The language is colorful and the memories and recollections worth cherishing.