Captured In Time: The Enigmatic Artist Charles Lees

Charles Lees was born in 1800 in Cupar, Fife. And while digital maps don’t offer an option to calculate the distance (in time) from Cupar to The Old Course by carriage, on foot it is three hours, and by motorcar (sadly, invented six years after Lees’ death in 1880), it would have taken only 15 minutes.

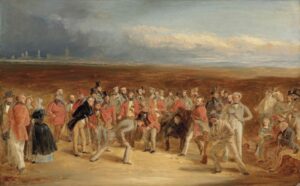

However, it must be said, Charles Lees was not a golfer. But he would leave—for history—a seven-foot incandescent canvas with one of the most iconic and emblematic portraits ever made of the game, in 1847, immortalizing the 1844 Grand Match at St. Andrews, entitled, “The Golfers.”

As a young man, Charles Lees trained as a painter in Edinburgh with the eminent Scottish portraitist, Sir Henry Raeburn. Incredibly, Raeburn, himself, painted John Campbell’s portrait (one of the featured contestants in The Golfers – right side, grey suit, standing) twice before, once nearly 50 years before Lees conceived of his great golfing scene, when Campbell was just four years old, and an orphan. That portrait today hangs in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

By the 1830s, Lees is listed as living at Nine Elder Street in Edinburgh’s New Town, which is (not coincidentally) one block from the Scottish National Portrait Gallery. He later moved to 19 Scotland Street in the 1850s, fully three blocks further away.

SCANDAL

At 32 years of age, Lees was swathed in scandal, having influenced a young lady nearly half his age (18) to run away with him to elope, against the express wishes of her parents. One contemporary account intimates that she stood to inherit a substantial fortune. In particular, two accounts make for tabloidesque reading:

Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle

Sunday, April 22, 1832

“Information was given at Bow Street on Wednesday, that the family of A. Christy, Esquire, of No. 8, Grove Terrace, Regents Park, was thrown into a state of the deepest distress on Monday night, between 8 and 9 o’clock, in consequence of the elopement of Miss Elizabeth Christie, a young lady about 18 years of age, with a portrait painter, from Edinburgh, of the name of Charles Lees. The unhappy relatives immediately issued the following handbill and dispatched persons in every direction in quest of the runaway. “Eloped between 8 and 9 o’clock this evening, from the house of her father, Archibald Christie, Esquire of No. 8, Grove Terrace, Regents Park, Miss Elizabeth Christie, a Ward of Chancery, aged about 18, rather short and stout, pale face, with dimple in her right cheek, dark brown hair, dressed in a cloak, with a squirrel boa, and straw bonnet. She speaks with a Scotch accent; supposed to have eloped with Mr. Charles Lees, portrait painter, of Edinburgh, about 5‘9“ in height, swarthy complexion, pitted slightly with the smallpox, black eyes and hair, and large black whiskers under his chin. If these parties present themselves at any Church to be married, it is requested that the young lady may be given in charge to the police, to be delivered to her father, who is her guardian appointed by the Court of Chancery, and they shall be handsomely rewarded for their trouble. Tuesday night, April 17, 1832.” An application has since been made to the Vice Chancellor, who has issued his order, directing Lees to appear before him, and restrain him from marrying the young lady.”

The Kerry Evening Post

Wednesday, April 25, 1832

“On Tuesday night, about 9 o’clock, the family of Archibald Christie, Esquire, of No. 8, Grove Terrace, Regents Park, London, were greatly alarmed, on account of the disappearance of Miss Elizabeth Christie, a ward in Chancery. Every search and inquiry was made for her by her friends, but without success. It was at last ascertained that she had eloped with a Mr. Charles Lees, an eminent portrait painter, from Edinburgh, who had recently formed an acquaintance with her, and to whom it is supposed she was much attached. Messengers were sent off in all directions to endeavor to trace the fugitives, and Mr. Christie, who is the young lady’s guardian, appointed by the Court of Chancery, immediately gave information to the commissioners of the new police of this circumstance, and directions were given to the police constables at the different station-houses to apprehend the parties if possible, of whom a very minute description was given. Miss Christie is only 18 years of age; rather embonpoint (i.e. plump), and a very accomplished and interesting young lady. On coming of age, we understand, she will come into possession of a very large fortune. The gallant is a dark-complexioned young man, and slightly pitted with the small-pox. It is strongly suspected that the lovers have directed their course towards Gretna (on the border with England).”

Highbrows will associate Gretna with the name, “Gretna Green,” a place traditionally associated in literature and poetry with eloping English couples because of the more liberal marriage provisions in Scots law compared to those in England. Gretna’s claim to fame arose in 1753 when an Act of Parliament was passed in England providing that if both parties to a marriage were not at least 21 years old, consent to the marriage had to be given by the parents. However, this Act did not apply in Scotland, which allowed boys to marry at 14 and girls at 12, with or without parental consent. As a result, many English elopers fled, and the first Scottish village they reached was often Gretna. The act was repealed in 1849, sadly 17 years too late for the fretful and disapproving parents of enterprising young Elizabeth.

I, indeed, found a record of their marriage registry at Gretna Green, as the bride’s father feared, dated April 25, 1832.

FAMILY LIFE

The following year, the besotted couple embarked for six months in Rome for Charles’ further study, during which time their first son was born, Archibald Romulus Reeves Lees, clearly named, in part, in honor of the founder and first king of Rome. (It appears Archibald had no twin, however!) Census records show eight births in all—5 sons and 3 daughters—two of whom (sons, specifically), I am led to presume, perhaps died in infancy. Archibald, however, lived 14 years beyond his father’s lifetime.

Following their stint in Rome, the Lees family returned to Edinburgh, where Charles established himself as a portrait painter of high repute. Lees was elected a Royal Scottish Academician, and from the 1840s, built himself a reputation as a specialist in depicting sporting subjects, “The Golfers” being his first major sporting picture. (A rare full-size sketch of The Golfers sold at auction in 2012 for 337,250 GBP, or just under half a million U.S. dollars, three times the auction estimate. The original belongs to the Scottish National Gallery.)

THE GOLFERS

Two asides… Interestingly, the aforementioned Balcaskie is a 17th century country house in Fife. The Anstruther family claims ties to that region dating to the 12th century, and—even today—Toby Anstruther, his wife Kate, and their family, make Balcaskie their home.

Additionally, one of the chief contestants seen in the work, John Campbell (right side with grey suit with high collar), was a founding member of North Berwick Golf Club as well as a member of the R&A. He presented North Berwick with the Glensaddell Gold Medal in 1832, a prize competed for from 1832 to 1849. Playfair (top hat, putting), Campbell’s match play partner in the painting, won the Berwick medal twice. One of their opponents in the painting, Sir David Baird (foremost, leaning forward), won the medal five times, including—in the tradition later known best as a result of the Open Championship belt—three years in a row from 1847-1849, making it his for keeps and ending the competition for the prize, forever. Mind you, Baird had also won the medal in 1840 and in 1841, successively. It was Playfair himself that crushed Baird’s bid to keep the medal forevermore in 1842, just two years before the events shown in the painting. It surely must have been a grand match, indeed! (The North Berwick medal recently sold at Graham Budd Auctions in London in 2006 for $29,506. Lees’ original oil-on-paper study for John Campbell in “The Golfers” sold at Bonhams in 2010 for $16,785.)

CURLING

Wee Nip readers may be less familiar with a monumental companion to The Golfers, which followed two years later, entitled, “The Grand Match at Linlithgow Loch,” in which a similar scene unfolds but—this time—for the sport of curling. Like The Golfers, this has been called, “one of the most important sporting paintings of its period.”

A review of the winter scene, on exhibit later at the Royal Scottish Academy, claimed:

Dundee, Perth, and Cupar Advertiser

Tuesday 12 March 1861

“The first picture specially to attract attention—at any rate by the numbers examining it—is “The Grand Match of the Royal Caledonian Club at Linlithgow, between the North and South sides of the Forth,” by Charles Lees, RSA. This picture was much spoken of before the exhibition, and there was a general curiosity as to what it would turn out to be. Perhaps some expected too much, and have been disappointed. The generalities of those who have examined it, I venture to say, have been gratified by the examination, and the gratification has been the greater according as they knew a large number of the persons whose portraits are given. Let me say, however, that, as a picture it does honor to Mr. Lees, apart altogether from the interest which the numerous portraits necessarily give it. These portraits number about 50, and, if I may judge by those of gentleman I know, they will be found faithful.”

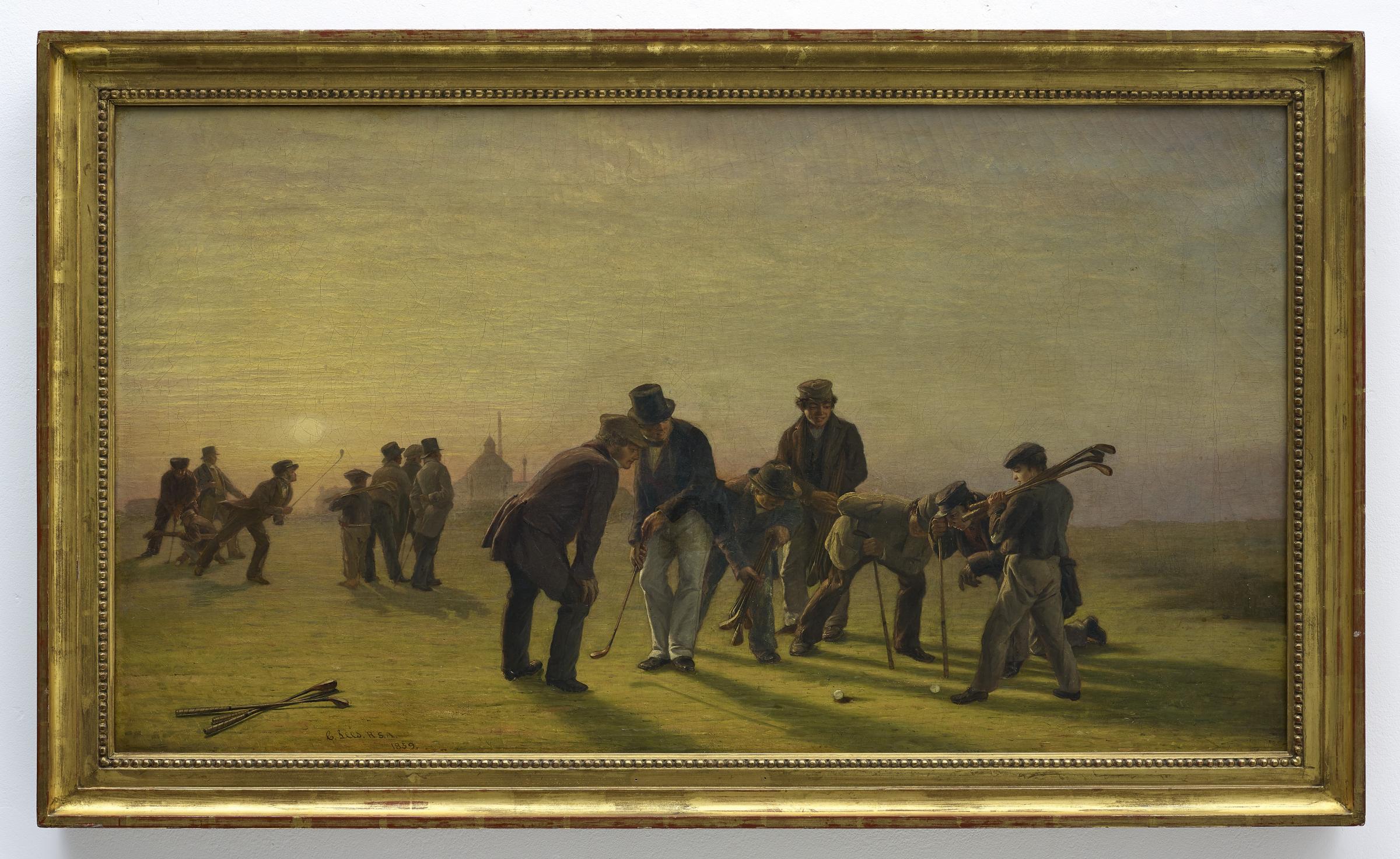

CADDIES AT MUSSELBURGH

Having cemented his reputation for sporting pictures, in 1859 (the year before the creation of The Open Championship), Lees produced “Summer Evening on the Musselburgh Golf Links,” showing caddies chasing the sun for an elusive final holes before sundown. According to a November 1914 Golf Illustrated article, Summer Evening on Musselburgh Golf Links remained long undiscovered because an early buyer, interested not in the subject but in the artist’s work, removed it from the Royal Scottish Academy to his residence in Canada. Its accessibility was suspended until the private buyer’s son, an avid golfer, came into possession of it.

The heir, Mr. Walter Brown, was soon urged to permit a reproduction, for which purpose it was shipped by the American branch of Arthur Ackermann & Son to Munich in 1913 where a photogravure plate was made. The painting was returned barely in time to avoid the outbreak of WW I, and was lost for a time. Golf Links to the Past, a shop at the Lodge at Pebble Beach, has one such reprint on sale today for $19,500 and writes that the original painting, “has now turned up, and been verified as genuine by an Edinburgh art historian (ex-National Portrait Gallery). The original plate, from which only a few prints were struck, is believed to have been destroyed during the war. It’s also believed that there are only a handful of surviving examples of this print in the world.”

DEATH

Charles Lees died in Edinburgh on February 20, 1880, at the age of 80, and was buried with his wife Elizabeth Christie (who passed 15 years previously), and their children, in Warriston Cemetery. Of numerous press accounts, the following is the most complete:

The Saint Andrews Gazette and Fifeshire News

Saturday, March 6, 1880

On Saturday evening, Mr. Charles Lees, RSA, died at his residence at Scotland Street, in the 80th year of his age. He had been ill for about three weeks, and seem to have rallied to some extent, but was seized with a more severe attack on Saturday night, when he peacefully passed away. Mr. Lees was noted both as a portrait and landscape painter. In his early days he spent a considerable time in Rome and other parts of Italy, and had command of both the Italian and French languages. His early pictures were of an exceptionally superior character, and are spoken of as excelling almost anything now produced at the Academy. Later he took to painting outdoor recreation scenes, more particularly those of winter, such as curling and skating, and in these were unequaled. They were very remarkable for the striking likenesses they contained of noted personages who took an interest in the games. This was specially the case with the well-known picture of the Royal Caledonian Curling Match at Linlithgow Loch, and excellence engraving of which is still in demand. The original, if we are not mistaken, is now in the possession of Mr. Charles Cowan of Loganhouse, the only survivor of those who were at the starting of the Royal Caledonian Curling Club. Another picture by Mr. Lees which obtained a wide circulation as an engraving was a golfing scene, where, as in the case of the curling match, the portraits of a number of gentlemen interested in the ancient game or given. An outstanding portrait amongst the many sent out from his studio was that of the late Mr. Adam Black—the likeness being an extremely speaking one. More recently Mr. Lees devoted himself to landscape painting, the views being taken in the course of his summer excursions in the country. These, as a rule, were exceedingly true to nature. They were carefully painted, and executed also with effect. “The Cottage on the Cliff—Thunderstorm Approaching,“ in the present exhibition of the Royal Scottish Academy, executed by him, as it has been, in his advanced years, is regarded as almost equal to anything recently done in that particular line. He is represented in the National Gallery by “The Summer Moon—Bait-Gatherers.“ Mr. Lees was born at Cupar-Fife in 1800, and held the position of an Academician before the Royal Scottish Academy obtained its charter in 1838. He took great interest in all that concerned the welfare of the Academy. For the last 12 or 13 years he held the office of treasurer, and was most conscientious in the discharge of his duties. In husbanding the funds and looking after the financial affairs of the Academy, he was probably never excelled by any of his predecessors. Mr. Lees was a gentleman of amiable disposition and comely appearance. In his latter days, when misfortune fell upon him as trustee in connection with the City of Glasgow Bank, he must have suffered from anxiety; but the pleasant-looking old man bore up bravely, and has gone to his rest leaving behind him an amount of affectionate regard and esteem for his memory won by but few. Mr. Lees is survived by three sons and three daughters. One of the former is a fleet surgeon.

– Robert Birman