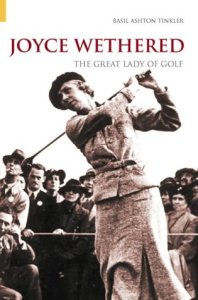

Joyce Wethered: The Great Lady of Golf

Joyce Wethered: The Great Lady of Golf (Tempus Publishing, 2004)

Joyce Wethered: The Great Lady of Golf (Tempus Publishing, 2004)

Review by Robert A. Birman

Rereading Basil Ashton Tinker’s scrupulous expose on the legendary lady of the links, Joyce Wethered, I was reminded of the J. Paul Getty quip, “The meek shall inherit the earth, but not the mineral rights.” Joyce Wethered: The Great Lady of Golf (Tempus Publishing, 2004) chronicles a remarkable life of relative privilege (Wethered’s progenitors gained wealth via ownership of several coal mines), yet filled with the usual grit and hard work that characterizes a champion.

This “great lady” lived 96 years and one day. She was known as Lady Heathcoat-Amory for the majority of her years, and in spite of her fame and stature, she remained humble and charitable until her final days in 1997.

To say that Wethered was a dominant competitor grossly understates the case. She won 33 consecutive matches in the English Women’s Amateur tournament, owning the title exclusively from 1920 through 1924 – (age 19 to 23.) She also won 36 of 38 matches in taking the British Women’s Amateur championship four times in a span of seven years. She retired (for the first time) in 1925 prior to her 24th birthday.

To say that Wethered was a dominant competitor grossly understates the case. She won 33 consecutive matches in the English Women’s Amateur tournament, owning the title exclusively from 1920 through 1924 – (age 19 to 23.) She also won 36 of 38 matches in taking the British Women’s Amateur championship four times in a span of seven years. She retired (for the first time) in 1925 prior to her 24th birthday.

Out of popular demand and national pride, Wethered returned to competition in 1929. The British Amateur was returning to St. Andrews and the nation could not bear to think of watching the trophy placed in the hands of the U.S.A.’s Glenna Collett, who was on an international tear of her own.

While setting a new single-round scoring record, Connecticut’s Glenna Collett won the U.S. Women’s Amateur in 1922 and again in 1925. She then repeated the feat in 1928 and 1929 (incidentally, she also won in 1930!) Echoing Wethered’s supremacy, Collett recorded 16 consecutive tournament victories and was widely regarded as the only major challenger to Wethered’s dominance.

Ashton Tinkler’s tale opens with the 1929 British Amateur and details nearly every step of the championship’s progression. Playing in front of 3,000 spectators at the final on the Olde Course, it was Joyce and Glenna, as predicted. Joyce was down five after the front nine. She closed the gap to two after eighteen. After 27 holes, she was four up, and as is fitting, she closed out the match on the famed 17th hole, 3-and-1. Having accomplished her goal of winning at St. Andrews, she withdrew from the championship scene once more, this time for good.

NWHickoryPlayers.org readers will likely already know Bobby Jones’ praise of Wethered. “I have not played golf with anyone, man or woman, amateur or professional, who made me feel so utterly outclassed.” This accolade followed a 1930 outing at St. Andrews in a stiff wind in which the players teed from the rear tees. Wethered shot a 75.

There are ample insights into Wethered’s reflections on the game scattered throughout the biography. Of St. Andrews, she says, “To become a genuine lover of St. Andrews (one) needs plenty of time and experience. I stayed a fortnight on my first visit and the last week passed in a flash – one heavenly day after another. It took the whole of the first week to sort out the holes and even to begin to understand the links; but ever since then the Old Course has stood alone in my estimation and I love every hummock of it. When I saw all the famous holes which have frequently been written about, I found that they were quite different from what I expected. I can safely say that the two holes that frightened me more than any others I have ever seen were the eleventh and the seventeenth. There could scarcely be on any course two more alarming or awe-inspiring holes. I have played them both at very critical moments, so I ought to know what a terrifying test they can be.”

Like Jones, Wethered competed only with hickory clubs even in 1929 as she returned to the British, in spite of the fact the steel shafts had been sanctioned. Bernard Darwin, commenting on steel’s ability to reduce the side spin, famously quipped, “Never again would anybody be able to write, as did a facetious friend of mine, to the maker of a patent club, ‘it has added fifty yards to my slice.”‘ Hitting down the middle wasn’t a concern for Joyce Wethered. She seldom did anything else.

At the inauguration of the Curtis Cup in 1932, Joyce was asked to serve as its first captain. She agreed, and elected to play as well with disastrous results. The team of Great Britain and Ireland lost every match on day one but ultimately made a match of it, eventually coming up short. The media blamed the player/capital concept as the U.S. captain had her team practicing foursomes for days prior and Wethered’s team’s arrival at tea time the day before the start of the competition.

As a result of the Depression, the phenom was forced to find employment, and took a post managing the golf department at Fortnum & Mason. In 1933, Spalding offered her a deal to market steel shafted golf clubs in her name. Examples of these are present in the market today, but rare. That same year, Walter Hagen’s publicist took her on, and in typical Hagen fashion, a whirlwind U.S. exhibition tour was proposed. Fortum’s board agreed to furnish her full salary in spite of a three-month deal to play golf throughout the United States. Her brand status was that important.

All of this created a controversy with regard to her status as an amateur. For twenty years, from 1934 to 1954, the R&A declared Wethered ineligible to compete as an amateur. That year, her book “Golfing Memories and Methods” was published and the following year John Wanamaker Department Store in Philadelphia invited her to represent their wares.

All of this created a controversy with regard to her status as an amateur. For twenty years, from 1934 to 1954, the R&A declared Wethered ineligible to compete as an amateur. That year, her book “Golfing Memories and Methods” was published and the following year John Wanamaker Department Store in Philadelphia invited her to represent their wares.

As she set sail for her ambitious U.S. Tour, supported by media endorsements from Gene Sarazen, she found herself having to conform to brand new equipment rules, playing a larger diameter ball in the U.S., and the smaller, more favored ball, for exhibition matches in Canada. She said she always preferred the smaller ball as it gave her greater distance off the tee.

It was decided that foursomes would maximize public interest, and indeed they did. All players drove from the same tees and no putts were to be conceded. The list of courses she visited is a Who’s Who of the American top 100.

She was an instant media sensation. Witness this tasty morsel from George Trevor writing in “The Sportsman,”

“A stranger in a strange land, she seemed a bit bewildered and embarrassed by the battery of cameras trained upon her, by the babble of orders from the news photographers, and by all the fuss and fury with which America greets its sports celebrities. Obeying the obvious command, she forced a thin smile.

Finally the hubbub was stilled, the cameramen were shooed away, and the supple girl in blue, who gave the impression of slightness, despite her five feet eleven inches, took her stance and addressed the ball. All eyes were fixed on the slim girl with the typically English face.

She had lost any trace of self-consciousness as she settled her feet firmly, fingered the club with the assurance of one who knew what it was all about, and started a swing which for pure grace has never been equaled, no, not even by Bobby Jones himself. The slender girl in blue was in her element at last.

Genius is a disquieting thing. it defies analysis, cannot be translated into words. That graceful fluid swing epitomized the effortlessness of art. Even tyros in the gallery realized, perhaps subconsciously, that here visualized in the flesh, was a living picture of everything the textbooks and theorists had written about the perfect golf swing.”

She teamed with and against legends of the era including Ouimet, Sweetser, Jones, Collette-Ware, Zaharius, Armour, Sarazen, and more. In three months, she traveled 15,000 miles and competed in 53 official matches, breaking women’s course records on 34 occasions. The entire itinerary is detailed in an appendix within the publication.

The author has a minor habit of restating earlier declarations about the subject throughout the tome (I counted the Jones quote no fewer than three times), often adding subtle new context. His account of competitive matches is thrilling and clear. As with so many books about the period, there are images over a handful of pages and one can only dream of time travel to satisfy the desire to witness her understated manner and cool disposition of her opponents. She was said to be within herself on the course, not unlike the nature of Sir Nick Faldo at his zenith.

“I feel nobody could push me off my right heel at the top of my swing,” said Wethered in a series of instructional pieces for the Daily Telegraph. “And at the other end, I feel nobody could push me off my left foot.”

Thankfully, archival video of Wethered’s swing can be seen, along with that of Jones and Vardon, in the same reel at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ivo0n49U3aI.

We all would do well to emulate her action, sans the long flowing skirt, buckled heels and cloche hat!