Tacoma’s Jim Barnes was a thinking man’s golfer

Born in Cornwall, England, Jim Barnes came to the United States in 1906 and became one of the world’s finest players. He won the first PGA Championship in 1916, defeating Jock Hutchinson in the final match, and successfully defended the title in 1919 after a two year lapse due to World War I. Jim won $500 and a diamond medal for each victory. He won the 1921 U.S. Open, defeating Walter Hagen by eight strokes at Chevy Chase Club, near Washington D.C., and the 1925 British Open at Prestwick Golf Club in Scotland. He was a four time champion of the Northwest Open. Jim was the golf professional at Tacoma Country & Golf Club from 1911 to 1915.

(Note: Portions of this article originally appeared in the May 1964 issue of Golf Journal.)

A twinkle came into the eyes of the tall, angular, white-haired man as he sprawled in a captain’s chair. He was studying a rough sketch of the hole which everyone suspects will be the most troublesome of the lot in the 64th U.S. Open Championship at Congressional Country Club, Washington, D.C., next month.

“The sixth, eh?” he said, “456 yards, fairway rises to a crest about 300 yards from the tee. That’ll be quite a second shot they’ll have to play. If it’s soft in the tee-shot area, they won’t get any roll. Narrow opening between that big pond on the right and front corner and the bunker on the left. Bad trouble to the right and back of the green. Ditch and out of bounds along the right side of the fairway. Heavy rough at the left just in front of that bunker. Quite a hole . . . quite a hole. Be a number of 5s there all right – and 6s and 7s, too.”

The twinkle was gone now but its meaning was clear. There was nothing Long Jim Barnes would rather do than turn back the clock four decades and apply once more to the challenge of a hole like the sixth that combination of cunning and skill that made him one of the world’s outstanding golfers between 1914 and 1930.

The Open returns to the nation’s capital next month for the first time in 43 years – since 1921 at the Columbia Country Club when Jim Barnes all but annihilated a great international field and won the championship by nine strokes.

Of all the 62 Opens before or since, only one winning margin has been greater, and that was an 11-shot triumph by Willie Smith in 1899 when the competition was considerably weaker. Barnes’ rounds of 69-75-73-72 for 289 bettered Walter Hagen’s score by nine strokes, Chick Evans’ by 13, Bob Jones’ by 14, Englishman George Duncan’s by 16, Gene Sarazen’s by 22, and Jock Hutchison’s by 23.

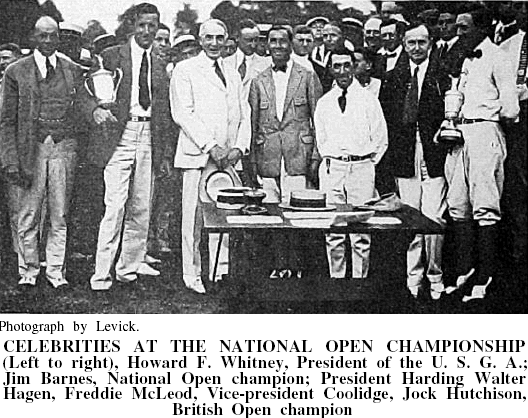

“You’d have to call that championship the crowning point of all the golf I played,” Barnes said as his right leg sprang up and deposited a well-polished size 13 shoe on the top of a radiator. “Winning by nine strokes against a field like that and then having the trophy presented to me by the President of the United States! Warren Harding loved golf, you know . . . did a lot for it during the time he was in office . . . and he was there every day of the tournament. So was Calvin Coolidge, who was then the Vice President.

“A day or two after the championship, President Harding had Freddy McLeod and me over to the White House for lunch. How many times does a winner get the trophy from the President and then have lunch with him? I won a lot of championships – the first PGA, in 1916, and again in 1919 when it resumed after the War; the British Open, Western Open three times, Southern Open, Southeastern Open, Northeastern Open, North and South Open a couple times. . . But this one meant more to me than all others combined.”

“You know, there’s a story I don’t think too many people know about,” Barnes went on. “During the winter of ‘21, probably late January or early February, I went to Florida for a couple tournaments and on the way down I stopped off at St. Augustine. I’d never played the course there and I’d heard it was a good one. I walked into the club and the first person I saw was none other than Freddy McLeod, my closest friend in golf and still a close friend – you know he’s still at Columbia, been there 52 years.

“Well, I say to Freddy, ‘What are you doing here?’ and he says ‘I’m here with the Big Boss.’ ‘Your club president?’ I ask, and Freddy says ‘No, no, no. The Big Boss.’ I say, ‘What other boss you got?’ and Freddy breaks out in a big grin and says ‘The Big Boss… Harding!’

“Now Freddy’s always pulling my leg, so I say ‘All right, Freddy, I’m from Missouri – you show me.’ He says ‘follow me’ and we go into a room off the locker room where there’s a couple fellows sitting around having lunch. Sure enough, it’s President Harding, and although I’ve never met the man before he jumps up and says ‘Jim Barnes, you’re just the man I’m looking for. Now I’ve got a partner.’

“Well, that was on a Monday and I was planning to pull out that night. I didn’t get out of there until Friday night. Each day the President and I would play a match against Freddy and a friend of the President’s, I think he was his campaign manager. Harding hadn’t taken office yet. In those days, they didn’t have the inauguration until March and so he was on a little vacation.

“Well, that was on a Monday and I was planning to pull out that night. I didn’t get out of there until Friday night. Each day the President and I would play a match against Freddy and a friend of the President’s, I think he was his campaign manager. Harding hadn’t taken office yet. In those days, they didn’t have the inauguration until March and so he was on a little vacation.

“When we finally left, the President said to me: ‘I suppose you’ll be playing at Columbia in the Open?’ I said I would and he said ‘I’ll be there.’

“He was, too, every day. When I putted out on the last hole, I walked over to him and the first thing he said to me was ‘Congratulations, partner.’ ”

The 1921 Open at Columbia was played in July, and a week or so before the championship a combination of blight and drought severely damaged the greens. The USGA Green Section, which had been formed only seven months before, tackled the problem with all possible resources of the time but, at best, the greens were in spotty shape for the championship. In recalling the Open that year, Gene Sarazen wrote: “There isn’t much I care to say about my showing. Jim Barnes brought in a commendable total of 289 and nosed me out by 22 strokes. Barnes was about the only player in the field who could cope with the greens.”

The blight and the drought caused one of the earliest cases of brown patch in the Northern climates, and Columbia was faced with the choice of trying to improve the putting surfaces so they would not be too bumpy.

“They told me they put down a mixture of charcoal ground up very fine, almost like dust, and very fine sand,” Barnes recalled. “There were patches where there was no grass at all and then other spots where the grass was all right. They wanted to make it as level as they could but the mixture made it so slick there was nothing for the ball to grip when it rolled. They did the best they could but the greens weren’t good, and when I got there all the fellows were so upset they wanted to go home.

“I didn’t get to Columbia until the day before the 18-hole qualifying round. That spring, I developed a carbuncle on the back of my neck and the doctor I went to see in Pinehurst on the way home to New York put some ointment on it and told me to forget it. By the time I got home I couldn’t move my head and the pain was so severe I could hardly stand it. A doctor friend of mine operated on me in New York and, against his wishes, I went over to the other side to play in the British Open at St. Andrews. The infection had spread through my system and I was so weak I could hardly get out of bed. On the boat going over, five or six other carbuncles broke out. I never was able to get through more than nine holes in a practice round but I still was a contender until I just plain ran out of gas on the last nine holes of the championship. I shouldn’t have gone but I did get a good rest on the boat coming back because there was a coal strike in England and the fuel we took on was like dust. It took us eight days to make a trip we should have made in five and I was feeling a lot better when we got to New York.

“I was still being extra careful about my health and since I was hitting the ball well, and knew it, and since it was so darned hot in Washington, I decided one practice round would be enough at Columbia, which I had never seen before, incidentally. The day I got there was a bad one, hot and humid, and after I’d played the first four holes I said to Freddy McLeod, ‘Let’s go back to the clubhouse.’ We played in on the 17th and 18th – but that was all. Two-thirds of the course was completely new to me when we played the qualifying round the next day. The greens didn’t worry me a bit. The other fellows had been there three or four days and had been playing 36 holes a day. The greens had upset them and the hot weather hadn’t helped their mental attitude either. I knew I was playing well, well enough to play any course, I thought.

“I went into the Open fresh. I led the qualifying with a 69 that broke the course record – first time I saw the whole course. Then I shot another 69 on the first round and led all the rest of the way.”

After 36 holes, Barnes at 144 had a four-stroke lead over his friend, McLeod, and Charles R. Murray of Montreal, with Bob Jones – then 19 and several years away from greatness – another shot back at 149. A 79 on the first round dropped Hagen, the pre-tournament favorite, out of serious contention; an 83 on the second round ruined the hopes of Hutchison, who had won the British Open the month before. Jones fell back with a third-round 77.

With a 73, Barnes’ lead after 54 holes was seven shots. He shot a steady 72 in the final round and waltzed into one of the most one-sided championships in history, nine strokes in front of McLeod and Hagen. Hagen tied McLeod by playing the last four holes 3-3-3-3 and sinking a 50-foot putt at the 72nd with President Harding sitting directly in back of the flagstick, just off the apron.

“I waved to the President,” recalls Hagen, “took aim at him and putted. It was one of the longest I ever sank. He got a big kick out of it.”

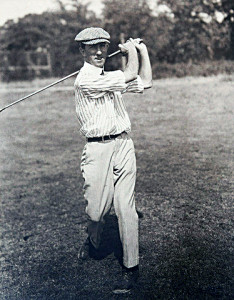

Meanwhile, Long Jim Barnes – all 6-3, 175 gangling pounds of him – was marching along the last few holes to the cadence of the Marine Band, which had come to honor the President and the Vice President.

“You could hear them playing all over the course,” Barnes remembers, “and when I came up to the last couple holes I marched right along with the songs. I didn’t know where the President was at the time and I thought they might be playing for me. You might say I had a victory march.”

His ever-present clover tucked in the corner of his mouth, Barnes finished with a flourish –sinking a good putt for a birdie 3 at the 71st and then playing a routine par 4 at the closing hole. He was ushered through the milling, cheering crowd – estimated at between 10,000 and 12,000 persons – and up to the President, who said at the presentation:

“It used to be thought that golf was a game for the elderly but I have come to the conclusion that every good contest in sportsmanship is fit for anybody in the world. I like to think of our country as a good sporting country. If I had my wish I’d want a republic where everybody can play.

“The beauty of golf is that everybody can play it, and he can play it at a minimum cost if he only keeps on the course. It is not becoming, perhaps, to philosophize about golf, but let me say to you, Mr. Barnes, that you are typical of the best in a noble and becoming sport. And let me say to you golfers who hope to better your scores – that takes you all in – I have seen the champion of this day drive into the rough and then stop and plant his feet and never drive until he was confident and sure of himself.

“If we only apply that poise and confidence to other things in life we will achieve even more than we have.

“The new champion has proved himself to be a player possessing courage, skill and poise. He has proved himself to be a sportsman in the finest sense of the word. He is an honor to the game he represents and to the title he has won.”

Although Long Jim Barnes never won the U.S. Open again, he went on winning championships for the next six or seven years, capturing the last of his big titles, the British Open, in 1925. After that victory, he was made an honorary lifetime member of the West Cornwall Golf Club in England, near where he was born and where he acquired his interest in golf, which was intensified after he came to the United States as a teenager in 1906.

After leaving steady tournament play in late 1920’s, Barnes served as professional at Huntington Crescent Club, Huntington, N.Y., later at the Essex County Country Club, West Orange, N.J., until his retirement nine years ago. Now 76 he lives with his wife of 41 years, Caroline, in East Orange, N.J., and limits his “competition” to a few holes with one club at Essex County, where he holds an honorary lifetime membership, and an occasional session on the putting green. Except for his snow-white hair, he looks much the same as he did during the 20’s, spry of step, and still gangling and lean, only eight pounds heavier than his “playing weight” four decades ago.

Proud of the part he played in helping to advance golf to its present popularity, he sees scores continuing to improve and even more people playing the game . , . “if there’s enough land around to accommodate them.”

“Golf, of course, has changed,” he said. “Today, there’s a precision-tooled club for just about every situation you encounter on a golf course. The equipment is better, the ball is better and the courses are kept in remarkable condition. Some of the fairways today are better than a lot of the greens we played on. Our fairways were mostly clover and weeds.

“But the players are no better. There are more good ones because they play so much more and practice so much more and there are more people playing golf. But if you brought back Hagen, or Jones, or Sarazen or anyone you wanted to name who had a good record years ago, they’d hold their ground now.”

That Jim Barnes was a thinking man’s golfer is illustrated over and over in the stories he tells –from his attitude concerning the spotty greens in the 1921 Open that caused most tempers to flare to his explanation of why he always carried a clover blossom in his mouth when he played.

“Everyone thought – and wrote – it was Barnes’ good-luck charm,” he said, his rugged features breaking into a wide grin. “They thought it was a four-leaf clover, but I’ll tell you a secret. I didn’t want to drink water while I played golf. So I always looked for the longest-stemmed blossom I could find and broke it off at the base. Then I put the stem under my tongue—not on top of the tongue, where I’d chew it – with the flowering part outside my mouth. The juice from the stem kept my mouth fresh and moist all the time. No matter how hot or tired I got, I never got thirsty.”

Year Championship

1916 PGA Championship

1919 PGA Championship

1921 U.S. Open

1925 The Open Championship