The Foulis Brothers: Scottish-American Golfing Pioneers

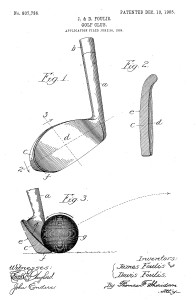

I purchased this Foulis-patent mashie niblick in March 2016 specifically for use at the 2016 International Match Play tournament in Philadelphia at the Philadelphia Cricket Club. The reason is simple. We play stymies in this event, and with the concave shape of this Foulis-model club, and the flat-lie of the leading edge (in combination with the loft), I have the belief that this is the ideal club for use on the greens when forced to jump an opponent’s ball. Below is a terrific history of the Foulis brothers, as well as links to the original patent for this club, c.1905. This club generates a tremendous amount of backspin on pitch or chip shots and feels as though it could be a great sand iron as well. The capital “E” on the club is MacGregor’s model designation for smooth-faced mashie-niblicks of the period. I’ve also seen one labled “C”, which was a lined face model. – Robert Birman

In 1996, golf historian Jim Healey published “Golfing Before The Arch; A History of St. Louis Golf’ that chronicled golf in the St. Louis region form 1895–1996. He interviewed dozens of area golfers and related individuals for the book including; Judy Rankin, Hale Irwin, Bob Goalby, Jay Haas, Keith Foster and Tom Wargo. More recently he has written club histories for some of the oldest St. Louis clubs, including Glen Echo CC (1901), Algonquin GC (1903) and Norwood Hills CC (1922) site of the 1948 PGA. A member of the Golf Writers Association of America, Jim has published dozens of articles related to St. Louis area golf and its history. His research led him to the Foulis family and their illustrious history as part of the growth of golf in the Midwest.

NWHP thanks Jim for gracious permission to reprint this article here.

- Please provide a little background on the Foulis brothers.

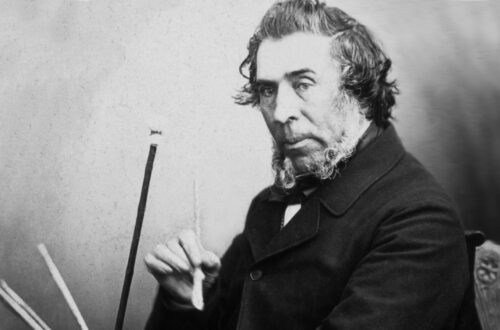

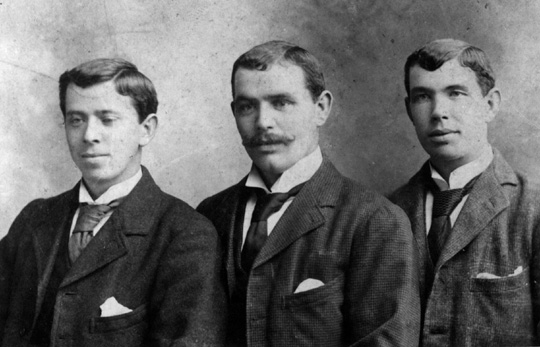

There were five Foulis brothers, Dave, Jim, Robert, John and Simpson. Of these, all but John were golfers – though John was an expert ball maker and did work as a bookkeeper at Chicago golf from 1901 to his untimely death in 1907 – and only Simpson remained an amateur throughout his life, while the remaining three were professionals at some of the most prestigious clubs in America. They were born in St. Andrews, Scotland and lived at 166 South Street, just four blocks from the Old Course. They came to America between 1895 and 1905 and made their mark on dozens of courses and clubs from Minnesota to Missouri and from Chicago to Denver.

They are all buried at the Wheaton Cemetery, adjacent to the Chicago Golf Club, the site where most of them made their mark and where Jim and Dave spent many years as pioneers of golf in the western United States.

- What interaction did they have with Old Tom Morris?

James Foulis Sr. was the foreman for Tom Morris at his shop in St. Andrews. James Sr. was recognized as an expert clubmaker. All the boys worked at one time or another in Tom Morris’ shop for their father. Their grandfather tended sheep on the Old Course when George III was King of England and prior to the war of 1812. Old Tom Morris took Robert under his wing for special attention and taught him how to make clubs, featherie balls, and about golf course design as they walked the Old Course in the evenings. He pointed out how the wind had shaped the course and how the sheep, lying against the mounds and bunkers to shield themselves from the wind, had shaped these with the help of Mother Nature.

Robert’s first design contract was given to him in 1889 by Old Tom for Ranfurly Castle Golf Club in Bridge of Weir, just west of Glasgow. An excellent moorlands course, it offered outstanding views of the Clyde Estuary. This was also near the home of legendary Scottish poet, Robert Burns. Following the construction of the course, the club sought out a professional for the new layout. With a personal recommendation from Old Tom, Robert was selected for that position, which he held for several years.

- How and why did they come to America?

In late 1894, following the construction of America’s first and oldest eighteen-hole golf course, Chicago GC, Charles Blair Macdonald wrote to Robert to come to America for the position of golf professional at his new course. Macdonald and the Foulis’ had met when he was a student at St. Andrews University, where Macdonald lived with his grandfather, and had obviously thought highly of their skills. Robert, who was still under contract to Ranfurly, would not think of breaking his commitment to them, so in his place he recommended his older brother Jim. Jim had learned his golf from Old Tom as well, and had also worked for Forgan & Company. An excellent player, he and Robert had had many great matches over the Old Course.

Arriving in this country aboard the SS Umbria out of Liverpool on March 11, 1895, it wouldn’t take long for the 24-year old to quickly make his mark. Jim immediately traveled to Chicago where he became the first golf professional at Chicago GC, and the first golf professional in the western United States.

In the summer of 1895, Jim cabled Robert that he had a contract for him to design a course in Lake Forest. Robert arrived on July 13, 1895, aboard the ship SS St. Louis by coincidence, and began work on the course over the next several months. The new Lake Forest CC opened in 1896 with their 9-hole layout. Today that course is part of Onwentsia Club.

Dave arrived in March 1896 and went to work with Jim at Chicago GC. In 1899 James Sr. and the rest of his family made the journey to Chicago where most lived for the remainder of their lives.

- What were Jim Foulis’ and the other brothers early years like in America, both as players and as architects?

In 1895, Jim was part of the eleven men who made up the field for the first U.S. Open at Newport GC. He shot a 176, finishing third behind Horace Rawlins and Willie Dunn with Rawlins shooting a score of 173. Jim was renowned for his driving ability, and was considered one of the longest drivers of the ball in the country for years. Records of exhibitions in which he participated, often with players like Alex Smith, Jock Hutchison, Willie Hunter and others, Jim would drive greens over 300 yards from the tee.

In 1896, in the Open at Shinnecock Hills, using a gutta-percha ball, Jim shot rounds of 74 and 78 for a 152 total to win the second U.S. Open. His two-round total stood as a record until 1903 when Willie Anderson posted a 149 for his first two rounds, while winning his second of four Open titles. Jim’s single round score of 74 also stood for still another year until Willie Anderson shot a 72 in 1904.

Robert competed in the 1897 Open at Chicago GC, finishing in a tie for 15th, while Jim was finishing third. Jim continued to compete in the Open through 1906, with Robert competing again in 1900 and Dave in 1904.

Simpson was a fine amateur and he competed in various regional and local amateur events for years, representing the Chicago GC. A banker by trade, he was a competitor at the 1904 Olympic Golf Matches at Glen Echo CC in St. Louis, where Robert was head professional. Simpson competed on the Western Golf Association team, headed by Chandler Egan, as they took on the Trans-Miss and U.S.G.A teams the day before the competition. In this ‘practice match’ the Trans-Miss team won the event. Shaking up the squad, Egan replaced several players, including Simpson, as the WGA won the team match and an Olympic Team medal was awarded to each member.

Jim took advantage of his newly earned reputation and he began to further his architecture career. In 1896, he traveled to St. Louis where he designed the original 9-holes for St. Louis Country Club at their original site. Seventeen years later, in 1913, St. Louis would move to their present site and the club contracted with C.B. Macdonald to design their new course.

From 1896 through 1927, Jim continued to design courses throughout the Midwest. Some of these include; Denver CC (1902), Geneva GC (1901), DuPage County GC (1901), Lake Zurich GC (1895), Kinloch GC (1898), St. Louis Golf Club (1898), Florissant Valley CC (1899), Milwaukee CC, Newspaper GC (1900) Memphis CC (1905), Hickory Hills CC (1923), Hillmoor GC (1924) Calumet CC (1911), Hinsdale GC (1898), Meadowbrook CC (MN), Edgebrook GC (1921), Bonnie Brook GC, Burlington CC, Nippersink Manor CC, Pipe O’Peace GC (1927) and Kent CC (1900). Lake Zurich, with a small membership on Chicago’s north side, is a course of only 2,865 yards and, according to its members, is exactly as Mr. Foulis left it over a century ago. While many of these courses no longer exist, one can see his influence on early golf as he created courses where none had previously existed.

Jim collaborated with Robert, and occasionally with Dave as well, as they designed and constructed additional courses. In many of instances, Jim did the routing of the course, while the actual construction was left to Robert. These include; Glen Echo (1901), Normandie (1901), Bellerive CC (1910), Sunset CC (1917) and Wheaton GC (1909).

- How did Robert end up in St. Louis while the other brothers stayed in Chicago?

Following Robert’s success at Lake Forest, C.B. Macdonald wrote a letter of recommendation for him and he traveled to Minneapolis where he built the Town & Country Club. He would also construct the original 9-holes for the Minikahda Club in 1898, and later worked with Willie Watson on the 2nd nine in 1906.

Robert continued designing courses on his own, though one would believe that he was in contact with his brothers on a regular basis for their input. Robert also assumed the role of golf professional and greens keeper at many of his courses. Robert’s designs include; Lake Geneva CC (1897), Meadowbrook CC (1912), Jefferson City CC (1922), Bogey Club (1910), Forest Park GC (1913), Log Cabin GC (1909), Triple A GC (1902), Ruth Park GC (1930), Riverview GC (1916).

In November 1900, Jim was contacted by Colonel George McGrew, founder of Glen Echo CC, to come to St. Louis and design the St. Louis area’s first 18-hole course. Jim arrived in January 1901, with Robert alongside. Together they began to layout and construct Glen Echo on over 350 acres of pristine land. The course opened on May 25, 1901. Jim returned to Chicago, while Robert stayed on as golf professional and greens keeper. He and Jim also designed the Normandie GC, which sits adjacent to Glen Echo and at one time their borders touched. Robert left Glen Echo in 1907 and moved to Normandie. Then in 1909 he began construction of the original Bellerive CC, which opened in 1910. He moved there and remained as their head pro and greens keeper until 1942.

- What was their relationship with other architects of the day?

Robert did construction for other architects, as they respected his talent in this area. One of these collaborations was with Tom Bendelow at Algonquin GC in St. Louis (1903), as Bendelow did the original 9-hole routing and then left the construction to Robert. Virtually every course built in St. Louis prior to 1930 had Robert’s hand on the final layout. As a superintendent he was second to none and many clubs had him on an annual retainer to insure that their course and greens survived the often difficult St. Louis summers.

Jim was the head professional at Olympia Fields during the construction of their original four courses. He preceded Jack Daray Sr. as professional there by a few years, and Daray, like other professionals of the day, moonlighted as an architect and built many other Chicago area courses. Though Jim played little or no role in the actual design of Olympia Fields four courses, his presence and background must have certainly made Bendelow, Watson, and Park give their work just a little extra to gain praise from the respected Foulis.

They also had a long-standing relationship with Donald Ross. The Dornoch native spent two years at St. Andrews in 1891-92 and would have come across the Foulis’ as he visited Old Tom Morris at the Old Course. He also worked at the Forgan & Company shop, likely alongside Jim Foulis. A year younger than Jim, and a year older than Robert, the three of them must have learned much from Old Tom in those days. They also competed together in the US Open in the early 1900’s.

Another local Chicago architect they knew well was Herbert J. Tweedie. An original member of Chicago GC, Tweedie worked closely with C.B. Macdonald. When Chicago Golf moved from their original site in Belmont to build their new 18-hole course at Wheaton, Tweedie and others stayed at Belmont and formed a new club there. In 1898, Tweedie teamed with Robert, Jim and H.J. Whigham (Macdonald’s son-in-law) as they added nine holes to the original Lake Forest Club, now renamed Onwentsia. Tweedie went on to build such outstanding Chicago courses as Exmoor, Flossmoor, Glen View, LaGrange and Midlothian. Interestingly, Tweedie was the manager for the A.G. Spalding business in Chicago, the firm that also employed Tom Bendelow as their spokesman and resident architect, but there is no evidence that Tweedie or Bendelow ever collaborated on a design.

As noted earlier, Robert worked with Willie Watson at Minikahda in 1898 and again in 1906. But for the most part, the Foulis’ supported each others efforts.

Robert’s work was also well respected by architects not generally thought of as being Midwest designers. When Harry Colt published his 1933 book, ‘Golf Courses: Design, Construction and Upkeep’ several of Robert’s architectural features were included as examples of good design features and he used Robert’s illustrations in his book.

- Being from St. Andrews, were they good players? Did they have a friendship with other significant players of the day?

In the 1880’s, their good friends, J.H. Taylor and Harry Vardon, had come to St. Andrews to visit and stayed with the Foulis family. During a friendly match over the Old Course, Dave and Robert had beaten their guests during one of their stays. Through the years, Robert and his brothers would compete in six matches with Vardon and various partners, with Vardon ending up on the winning side only once.

They also knew Sandy Herd and James Braid, who with Taylor and Vardon were the best players in Scotland and England.

Surprisingly, there is little record that they competed in The Open while at St. Andrews, though newspaper accounts have stated that they may have.

- What role did they play in the advances in technology taking place around the turn of the century?

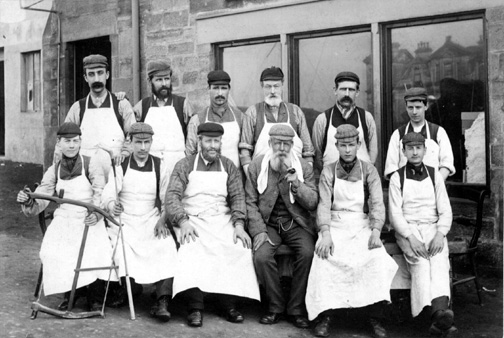

In 1903, a few years after the development of the Haskell ball in 1900, Jim and Dave were in their shop at Chicago GC experimenting with clubs and balls. They had determined that this new ball, while more durable than the old gutties, did not fly very far, except when ‘cut’ following several shots. They went into the fairway at Chicago GC and Jim and Dave began hitting the newly designed rubber-covered golf ball [the Haskell]. ‘Jimmy and I played one of the first dozen ever turned out’, Dave would recall years later ‘and even Jim couldn’t keep them from ducking to the ground just off the tee. We quit after a little while and rode our bicycles back to Wheaton. We remolded the balls, marking them the same as we used to mark the solid gutta-percha ones. That fixed them; Jimmy made ’em go after that. The trouble was that the covers were too smooth; they wouldn’t grip the air.’ In an interesting addition to this story, Coburn Haskell, the inventor of the rubber-coated ball, heard what the Foulis had done to his ball, and threatened to sue them. What the brothers were doing was buying his ball, marking them to make them fly better and then reselling them. Haskell eventually did nothing, but he did buy one of their molds to mark his balls as well!

The new Foulis brothers bramble-pattern balls, named appropriately the American Eagle, was made and sold by them for years, though it has been reported that they likely gave away as many balls as they sold.

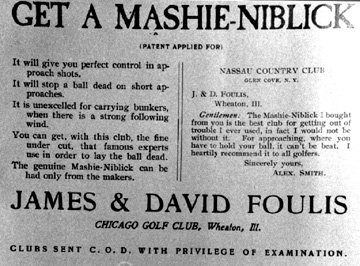

With the new ball flight, the brothers saw the need for a new club, one that fell between a mashie (5-iron) and the niblick (9-iron). ‘That brought up the need for a new club, for the old ones wouldn’t hold a middle distance pitch shot on the green with the new and faster ball. I took a niblick and remade it, and the result was the mashie-niblick!’ [Today a 7-iron]. Dave built it and Jim tested it. Together they applied-for and received a patent on the new club. They held the patent on the club until 1920, and received royalties on each club sold.

After leaving Chicago GC around 1916, Dave ran their highly successful J&D Foulis Company until 1921. At that time he moved to Hinsdale GC in Chicago and rebuilt it from a mediocre course to one of the finest in the Midwest. He remained there as pro-greens keeper for 18 seasons before retiring at the end of the 1939 season.

- Besides their work with early balls and clubs, it has been said that they were very innovative. Can you give us an example of their innovation?

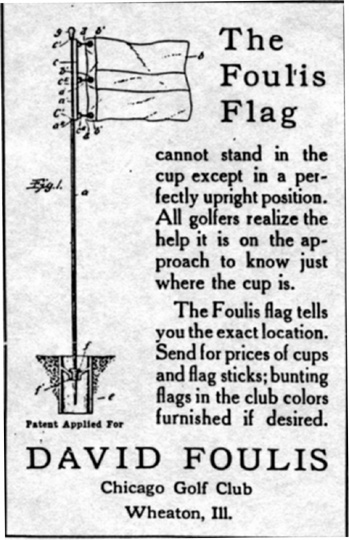

The brothers continued to be very innovative in other areas as well. One of the things we take for granted is the liner inside the hole. Early on, the holes were just excavated by the greens keeper and were not changed daily. The size of the hole would vary as player after player holed out. Dave made the following observation in a 1905 article in Golf Illustrated, ‘After a few days the hole would get deeper and deeper, as caddies would scoop sand from the bottom of the cup to make tees at the next teeing ground!’ While the liner is said to have first appeared in Scotland in the 1870’s, Dave Foulis brought the concept to America and sold the first metal liners around 1902!

Another of their innovations was the ‘Foulis Flag’ which took advantage of the new metal liner inside the cup to hold the flag in a ‘perfectly upright position’. The Foulis brother’s ad for this item was included in the Olympic Program in 1904.

10. Please shed some light on their instrumental involvement in the early formation of the PGA of America.

Robert White, who would become the first President of the PGA in 1916, was the head professional at Ravisloe from 1902 through 1914. The Illinois Pro’s had elected him president of their association. Years before professionals in New York or Boston pros organized, the Illinois association had their members playing in events and paying $2 per year in dues, along with $5 for each event. Then in 1915, White moved to Pennsylvania and the following year to Wykagyl as pro-greens keeper. While at Wykagyl, Rodman Wanamaker held the luncheon where the PGA was formed. White’s friendship with the Chicago golfers, and his reputation among the New York crowd, were enough to have him elected president, a position he held until 1920. As the PGA of America was being formed in New York, the Foulis brothers came together to get local professionals to support the new organization, and their friend White, as they helped form the first local ‘section’ as the Illinois PGA was founded. Dave Foulis served as president of the Illinois PGA for at least one term, and his obituary in 1950 stated that he and his brothers were instrumental in the founding of the PGA of America.

- What about their involvement in the Society of Golf Course Architects in 1948 (ASGCA)?

The Golf Course Architects Society was formed in 1947, two years after the death of Robert. There would have been little doubt that he would have been a Charter Member had he not passed away in 1945.

Jim Foulis, as noted earlier, had been a friend of Jack Daray Sr., one of the original founders of the ASGCA. Daray, like many local Chicago pros, was part of the original group that met at courses such as Ridge, Ravisloe and others, where they discussed course design, greens keeping and other aspects of golf course work.

Among the other original members of the ASGCA, the following had relationships with the Foulis’: Robert Bruce Harris, the first president, had worked with Robert at University GC in St. Louis in 1930. Their relationship with Donald Ross was noted earlier. Another founder, William Diddel, designed Crystal Lake GC in St. Louis in 1929 and remodeled Midland Valley in 1928 (forerunner to Meadowbrook CC, which, by coincidence, when the club moved in 1960 was designed by Robert Bruce Harris). Lastly, William Langford did work at Ruth Lake CC in 1926, where Jim Foulis was head pro, and at St. Clair CC (St. Louis area) in 1927, when Robert was at Bellerive.

- In general, what are the architectural merits of their courses?

Typical of the day, their courses featured the traditional style of that era; namely medium to small greens, teeing areas quite close to previous greens, bunkers that fell into two categories, greenside bunkers with flat bottoms and cross-bunkers featuring tall mounding facing the player and sand on the opposite side. Glen Echo had several of these features on the original layout of the course.

According to Keith Foster, who spent several years forming his business in the St. Louis community, the Foulis’ had several very unique, yet classical design characteristics. First among these were their placement of the teeing grounds and greens. With the greens in place, it appeared to Foster that the positioning of the tee-pads followed a hill-to-hill manner. At Glen Echo and Normandie, two of their early designs, many tee shots on 4-pars and 5-pars, carry valley’s to a landing area and then a carry to the green. This is also especially noticeable on their many outstanding par-3’s where you have an elevated tee to an elevated green. Many of these holes maintain the original design of a century ago and remain a timeless vision of their early golfing designs.

Another characteristic was how they tended to ‘cut’ their bunkers off prominent features around the course. If a green was situated on a plateau, for example, they would have cut-in a bunker underneath the plateau. This was similar to work done by Walter Travis on his designs.

Their bunkering was also more of a ‘splash out’ style as opposed to those with high deep faces. Foulis’ bunkers were not as penal, yet provided the degree of difficulty sought for errant shots. Lake Geneva CC, Robert’s 1897 design, has been virtually untouched through the years, with this bunkering style prominent on most of their holes.

Another characteristic, most often found when thinking of Donald Ross courses, is the slope of the greens and the ‘crown’ effect. The Foulis’ employed these on their courses, along with the occasional tiered-green. Many of the holes at Glen Echo, Normandie and Lake Geneva have sharp back-to-front or side-to-side slopes.

However, what was also unique about the Foulis brothers design was their use of features that are often attributed to other, more well-known architects. In 1901, James and Robert positioned cross bunkers on several holes at Glen Echo. These remained in play for years until removed in the ‘modernization’ trend of the 1950’s. Designers such as Colt and Allison, Raynor, Mackenzie and Tillinghast all employed this technique on many of their great designs at Shoreacres, Cypress Point and Baltimore Five Farms. This crossing-hazard on a number of their terrific short par-4’s would be scorned by many today, but was considered an outstanding design feature when constructed and remains so on courses bold enough to maintain them today.

- Glen Echo was not Robert’s first design but it was his first 18-hole layout. What are some of the unique characteristics of the course?

Glen Echo was founded by men with a passion for golf and the wealth to support it. Contracting with the Foulis’ was not surprising. James was well known in the area from his previous designs and having Robert join him was an unexpected bonus.

Glen Echo was the first St. Louis area course designed from its beginning with 18-holes. Before this, each course only had 9-holes, though many were contemplating adding their second nine to satisfy their members (no public courses existed in the St. Louis area until 1912). Foulis took the existing terrain, which featured several lakes, ravines, steep hills and rolling grounds and constructed what was called at the time ‘the finest links in America’, though as we all know that moniker was used to describe virtually every new course constructed for years, mostly to satisfy the young membership that they had made a good investment in their course!

Fifteen of the existing holes maintain virtually the same routing as it did a century ago. Through the years, the course has been lengthened from just over 6,100 yards to 6,500 with the addition of new tee boxes. The newest holes – the first and eighteenth – were added in 1927 when a new clubhouse was built that required a change in the original routing, and the sixth hole was added in 1914 when the original third and fourth were combined into one new hole.

Many of the greens require an uphill approach, some more severe than others. The first and third holes feature a severe uphill approach to a sharply sloping back-to-front green. The second, which has remained unchanged since opening day, features a slightly elevated tee to a left to right sloping fairway. Finding the fairway, you are left with an uphill approach to a medium size, fairly level green. The number three handicap hole, at 432 yards it is a well-deserved par. During the 1904 Olympic matches, many competitors found this hole the most difficult on the course.

Most of the par-3’s feature downhill approaches to the green, seemingly making the shot somewhat easier. However, even the 136-yard 14th, modeled after the short hole 8th at St. Andrews, requires an accurate shot to avoid the bunkering right and front left, or the steep falloff to the left. The twelfth, a par-4 of 406 yards, is another example of great design. An elevated tee to a hilltop 230-250 yards away with a grove of trees to the left. A good tee shot will leave you in the fairway atop the hill, about 150-180 yards out, facing a slightly downhill lie to the sharply uphill green; a very demanding shot. Bold hitters attempt to draw around the trees, or fly over them, hoping to land at the bottom of the hill in the only flat area on the hole. From there, it is but a hundred yards or so to the green. However, a false front fools many players, especially when the ball rolls back down the hill 30-40 feet, wishing they had taken one more club.

But perhaps the seventh best typifies the demanding shots required to mark a four on your card. At 468 yards, your tee shot must carry 260 yards over a valley to the elevated fairway, leaving you an approach of about 200 yards, once again all carry, to a green with three well-positioned bunkers. A false-front awaits the short approach, while shots coming in a bit too sharply will hit the green and roll through, leaving a very difficult pitch from thick rough to a green sloping away from you.

- Normandie Golf Club was built shortly following Glen Echo. Are there similarities between the courses?

The yardages are nearly identical, both just over 6,500 yards today (and both at just over 6,000 when opened) and both play to a par 71. A private course from 1901 to 1985, Normandie has been an outstanding public facility for the past 18 seasons. Known as a player’s course, most of the areas top amateurs joined Normandie for the competition and challenges.

Like Glen Echo, Normandie was designed on rolling hills, which allowed the Foulis’ to create their tee to green ‘pad’ holes. Holes that typify this are the opening par-4, (at 446 yards and the number one handicap hole) the seventh, eighth and ninth on the front, and the tenth, fourteenth, fifteenth and eighteenth. The par-4 tenth, at 420 yards, features a demanding uphill tee shot, and once there a downhill approach to a green with a creek in front. Par 3’s of 220-240 yards, par 4’s with approaches which must carry open valleys, and shorter par-3’s with steep slopes and tiered greens. Both courses also feature short, strategic par-4’s that tempt you to go for the green, risking the sand or rough nearby, while rewarding the successful attempt.

Normandie was the site of the first Missouri Amateur in 1905, making it the 6th oldest state amateur in the country, and site of the 1908 Western Open, won by Willie Anderson. It was also over these links that Jess Sweetser began to play the game as a youngster before his parents moved to the east coast shortly after the outbreak of World War I and the family changed their very-German name to Sweetser.

- Robert also designed the original Bellerive layout. How was it received in the area following his other two designs?

Apart from St. Louis CC, which remains the area’s premier course for most players, when Bellerive was built in 1910, as a collaborative effort between Jim, Robert, and Dave Foulis, it was hailed as the best course in the area. The course was longer than most courses of the day, at over 6,500 yards, and was built on over 350 acres. Bellerive was located less than a mile from both Glen Echo and Normandie, so the ground and other characteristics were similar.

As the years moved along, the growth of the airline industry had a dramatic impact on Bellerive. Located less than 5 miles from St. Louis’ Lambert Field, the airplane landing path was located almost directly over portions of the course. In 1955, a military jet crashed on the 15th fairway, killing the pilot and causing the Bellerive Board to begin to investigate a move to a new location, further west in St. Louis County. The club moved to its present site in 1960, when Robert Trent Jones selected the land for the club and built the existing layout. The University of Missouri purchased the land from the club for their new St. Louis campus, and for several years, through the 1960’s, used the clubhouse as their administration offices. Today, the University of Missouri – St. Louis (UMSL), occupies all of the former land.

- You mention Lake Geneva CC. Not many players have been to that course. How does it reflect the Foulis’ style?

Lake Geneva was originally a resort course for wealthy Chicagoans during the summer months. It has not changed that much through the years. At first appearance, it does not seem all that demanding. There are rolling hills, but they do not seem too severe. However, you will soon find out that looks can be deceiving. Sitting aside Lake Geneva, the land is generally fairly level. However, in keeping with the Foulis style, they used the land to create their ‘pad’ effect on several holes, while others have severe sloping fairways and greens that provide the ‘teeth’ for the hole.

The par-4 sixth is one such hole. At 396 yards, your tee shot is from an elevated tee to a slight dogleg right fairway. A good shot leaves you well inside 160 yards, but that’s when the real challenge begins. Your approach, usually from a slightly downhill lie, must cross a road, 50 yards short of the green, then a creek just on the other side of the road, to a green that slopes severely from back right to front left. Holding the ball to the right is almost impossible without hitting a high fade, and still gravity will take the ball to the left.

The par-3 ninth is another terrific hole. From an elevated tee, your shot must carry to the green, which slopes severely back to front, that is guarded left and right by Foulis-style splash bunkers. At 177 yards, the wind off the lake to your right affects many shots, forcing an extra club or two at times. Another par-3, the fifth, uses a bunker at front right and the slope of the green, left to right, to protect the hole and make earning par well deserved.

Even on this gently rolling terrain, Robert took advantage of each rise in the land to position tee or green to make the hole more interesting and the shotmaking just a bit more demanding.

- Another of their courses was Denver CC. Has this remained true to the Foulis’ design?

Unfortunately not. Denver CC, built in 1902, has undergone major renovations through the years by some of the great architects of the day. Some of those who remodeled Denver CC include; Harry Collis, William Flynn, William Diddel, Press Maxwell, Ed Seay and Bill Coore. It is interesting to note that Collis, who did the first redesign, was originally the greens keeper at Flossmoor in 1906, where he undoubtedly would have known the Foulis’ at Chicago GC. His redesign of Denver was done in the days just prior to World War I.

- What about their home life and their families?

James Foulis Sr. was married to Helen Foulis. He was born in 1841 and died in 1925. Helen was born in 1847 and she passed away in 1928, just a month before her son Jim Jr. In addition to their sons, they had two daughters, Annie, who was born in 1876 and died in 1963 and little Maggie who died in 1885 at age 4.

Robert had two children, Ronald and Eleanora. Ronald (1904) went on to become a successful lawyer, while Eleanora (1905) married Clarence Miller and they had two children, Laird and Robert Miller. When Robert Foulis settled at Bellerive in 1910, he stayed there for the next 32 years, living on Wheaton Avenue, just blocks from the front door of Normandie GC and within just a mile or so from Glen Echo and Bellerive. He remained pro-emeritus following his retirement in 1942. Robert died while on vacation in Florida on March 6, 1945 at the age of 71. His wife, Amanda, passed away in 1977. In 1995, Eleanora Foulis Miller passed away in Colorado. Her granddaughter, Malinda, found boxes in her attic that had been stored for years. In one of these boxes was glass jars filled with grass seed that Robert had brought from Scotland while looking for the perfect mixture to use on his courses. Ronald passed away in 1996 while living in California. Ronald had two children Ronald and Saralee, both of which reside in Pennsylvania.

Dave, born in 1868, had a son Jim, who was also a golf professional and who won the Illinois PGA championship several times. He was also a competitor in the first Masters in 1934 and competed in most of the PGA’s and U.S. Open’s through 1940. Dave died at age 82 in 1950. Dave had two children, daughter Jessie and son Jim. Named for his uncle and grandfather, Jim Foulis, Dave’s son, had a son, Dave Sr., who today lives in Massachusetts and a grandson, also named Dave, who also resides in Massachusetts. Dave Sr. has a brother Jim, who resides in Florida.

Jim Foulis Jr. was married to Jeanie Foulis but the union did not produce any offspring. He died of kidney failure on March 3, 1928 at the age of 57. Jeanie survived until 1960 at the age of 83.

Simpson was born in 1884 and died in 1951. His wife Alice was born in 1887 and she passed away in 1973. They had two daughters, Roberta and Margery. Margery passed away in 1956, while Roberta resides in Lafayette, Indiana today with her husband Don Stoike.

John Foulis, the eldest son, died in 1907 at the age of 42. There is no record that he married.

- How should the Foulis’ be remembered?

Robert, Jim and Dave learned their golf and their design from the master himself at St. Andrews. His love of the natural style of golf deeply influenced them and in the days without mechanical earth-moving equipment, they were forced to select the correct piece of land and position the holes on it for the most enjoyment possible. This was the era when golf was more sport than entertainment. The challenges lay in the bunkering, greens, hills, and lakes that dotted the landscape, keeping in mind the prevailing winds impact on each shot as well. At the same time, they provided generous fairways for their landing areas. Through the years many clubs have planted trees that were never meant to infringe on their original designs (or those of many other architects of this era). As a result, the open designs they created have been reverse-designed as players must maneuver around large trees instead of fairway bunkers or the more penal cross-bunkers.

However, the Foulis’ would best be remembered for bringing to the Midwest their love of the game. From the heart and mind of Old Tom they brought to their courses in Missouri, Illinois, Minnesota and Colorado, the shot values, features and memories of the best of golf from Scotland. They did it with class, an attention to detail, and a spirit that made them among the most respected and admired men of their day. While many of their closest friends are among the ranks of the great designers – Macdonald, Ross, Park and Bendelow – it would be safe to say that these brothers found solace and satisfaction in staying near the courses they created, while giving back to the members at those clubs, their knowledge and love of the game.