St Andrews—Cesspool to Sanctuary

The impact of Sir Hugh Lyon Playfair

As noted in Alistair Beaton Adamson’s biography of Allan Robertson (Allan Robertson, Golfer: His Life and Times published by Grant Books) St Andrews, as we regard it today, wasn’t always a hospitable place for golf.

Formally, golf was played at St Andrews for some time before Sir Robert Gordon’s book was published in the 17th century, The Earldom of Sutherland. In it, there is some of the earliest known documentary evidence, including reference to a license of January 25, 1552, granted by John Hamilton, “by the mercie of God archebishop of Sanctandros, primat et legat natie of the haill realme of Scotland” to the community of the city to rear rabbits “within the northern pairt of their commond linkes next adjacent to the Wattir of Edin” and confirming the “rycht and possessioun, propirtie and commnite of the daidis links in…playing at golf, football, schuteing and all gamis with all other manner of pastime…without ony dykin nor closing of ony pairt thairof fra thame or impediment to be maid thame their intill in ony tyme coming.”

Adamson writes:

Prior to 1585, the city had between 12,000 and 15,000 residents. The plague wiped out 4,000 of them in 1585 (roughly one-third). Town magistrates pointed out that the total decay of shipping and sea trades led to the removal of the most eminent inhabitants overburdened with new taxes to try to prop up the city coffers. Later, the King of England, William, directed the archbishop to relocate as well, a huge loss for the image and reputation of St Andrews. A report in 1697 (more than 100 years after the plague), states that considerations were being studied to relocate the famed university away from St Andrews and to the community of Perth, nearby.

Samuel Johnson on his tour of Scotland referred to St Andrews as “silence and solitude of inactive indigence and gloomy depopulation.” The city was in the depth of despair.

At the end of the 1700s, the houses were still built of wood with thatched rooves so there was a dampness, filthiness and absence of comfort. By the beginning of the 1800s, however—a few years before Allan Robertson was to be born—stone houses were being built and the streets were starting to be leveled. Formerly, they were so overgrown with grass that sheep grazed on them, as well as cows. As late as 1832, fourteen persons were attacked by cholera of which eight died.

The word “links” suggests a derivation from the Old English “hlinc,” meaning “lean.” The golf courses of antiquity had no uniform number of holes. They varied from the five holes on Leith links to 25 holes of Montrose. North Berwick had only seven holes because the golf was stopped by a wall across the links. Leith, of course, patronized by the gentry of Edinburgh, was later extended to seven holes but fell into disfavor. The Edinburgh clubs moved to Musselburgh by St Andrews had become the home of golf and eighteen holes became the standard round.

The sand and shingle, and indeed the sea, came up close to the site of the present clubhouse. In the 1840s, reclamation began under Sir Hugh Lyon Playfair. Later, behind a barrier of sunken boats filled with concrete—a system somewhat akin to the ships used alongside the Mulberry harbor at Normandy—countless thousands of dry town rubbish were dumped twelve feet thick to cover the sand and shingle and thus win the ground between the clubhouse and the sea.

So it was an ancient quiet town that Allan Robertson was born into, still not accessible to the world outside Fife. In 1829, when Allan was 14, the first stage coach started. However, there was not even pavement in the town by 1830.

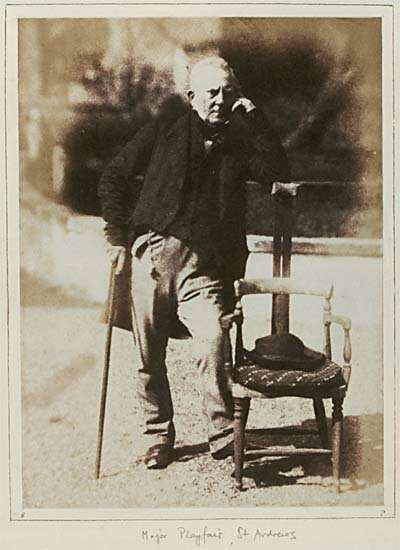

Twelve years later, Hugh Lyon Playfair, winner of the Golf Club golf medal in 1818 and later captain of the R&A, returned to St Andrews after army service in India. He looked upon the town as a “scene of neglect, isolation and decay.” The links were as slovenly as the town which was locked in filth as “lava entombed the Herculaneum of old.” With Playfair began “the erection of a town on the neglected site of a ruined city.”

WHO WAS THIS MAN?

This made me curious about Playfair, and led me to a biography written for The Calcutta Golf Society by Rollo Prendergast (Captain 2009). In it, he notes:

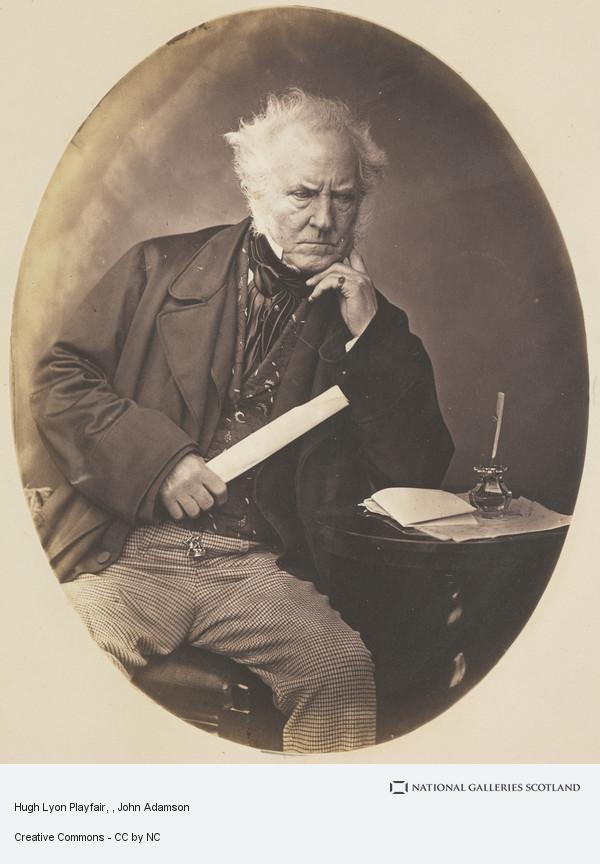

“The patriarch of this talented family was the Reverend James Playfair (1738-1819) who became principal of the United College at St Andrews in 1800 thus establishing the link with the town and university which was to be so firmly maintained by his descendants. The youngest of his four sons, James (1791-1866) became a prominent merchant in Glasgow; William Davidson (1783-1852) and Hugh Lyon (1786-1861) both had distinguished careers in the Indian army, subsequently retiring to St Andrews where they played a full part in local affairs, Hugh, indeed, becoming provost and overseeing the paving of the streets of the town. The eldest son, George (1782-1846) became a surgeon and also went out to India where he rose to the rank of surgeon-general.” (University of St Andrews: The Playfair and Diaspora Project)

The first record we have of Hugh Lyon Playfair’s connection with golf is his distinction of being the first winner of the Scotscraig Gold Medal in 1818 (Scotscraig Golf Club was founded in 1817 by some members of the St Andrews Society of Golfers, “who wished to play more golf than the Society’s occasional meetings afforded them”). He also won the R&A gold medal the same year. HLP must have been on home leave from India, between postings, keen no doubt to show off the prowess gained in Calcutta.

Hugh Lyon Playfair (HLP) born in Meigle, Perthshire, was a student at St Andrews University and served in India 1805-1817 and 1820-1834. He served in the Honorable East India Company’s Bengal Artillery Regiment, where he rose to the rank of Major. HLP later lost two of his three sons in action in the Anglo-Sikh Wars: Lt. William Dalgleish Playfair, of the 33rd Bengal Native Infantry died in 1846 (aged 24) at Sobraon and Lt. Hugh Arthur Playfair of the 52nd Bengal Native Infantry, in 1848 (aged 23) after the siege of Multan). The author of this 2009 biography notes that his own great grandfather, Brig. James Henry Prendergast, was also in the service of ‘John Company’: he was commissioned in the 29th Madras Native Infantry, the year before events of 1857 caused the British Crown to assume direct administration of India.

The official history of the Royal Calcutta Golf Club (the oldest golf club outside the British Isles) records the founding of the Club in 1829 as the Dum Dum GC. “We have much pleasure in publishing the following list of subscribers to the Dum Dum Golfing Club and congratulate them on the prospect of seeing that noble and gentlemanlike games establishing in Bengal” – Major HL Playfair and Dr Playfair (his eldest brother George) are listed among 30 such subscribers – “….The Dum Dum Links are said to be very inviting; they consist of fifteen holes, being a round of about two miles, and contain some very pretty and interesting hazards.” Oriental Sporting Magazine of December 23rd 1830.

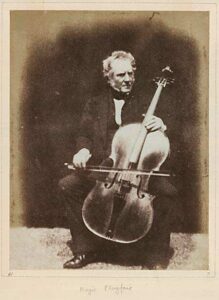

HLP seems to have been a polymath with interests in photography, gardening, music, golf, and civic affairs.

On his return to St Andrews in 1834, HLP “took up his residence in St Andrews, occupying his leisure with mechanical and mathematical pursuits, and furnishing his garden with those instructive curiosities, whims, and oddities, which have made it one of the ‘Places of interest to visitors’ and to which, with characteristic generosity, he welcomed all. His attachment to the City commenced when a student, and during his career in life that attachment never abated.” A biographical Sketch (D. Louden 1874) where this detail appears, goes on to paint a very different portrait of the thriving and select St Andrews we know today. “At the time of his return, St Andrews was fast dwindling into a state of ruinous decay. The streets were overgrown with grass, and it was no uncommon sight to see cows and pigs grazing upon them. Outside stairs, street projections, ruinous walls, dunghills, pigsties, and other abominations everywhere met the eyes, while noxious effluvia everywhere saluted the nasal organs.”

On his return to St Andrews in 1834, HLP “took up his residence in St Andrews, occupying his leisure with mechanical and mathematical pursuits, and furnishing his garden with those instructive curiosities, whims, and oddities, which have made it one of the ‘Places of interest to visitors’ and to which, with characteristic generosity, he welcomed all. His attachment to the City commenced when a student, and during his career in life that attachment never abated.” A biographical Sketch (D. Louden 1874) where this detail appears, goes on to paint a very different portrait of the thriving and select St Andrews we know today. “At the time of his return, St Andrews was fast dwindling into a state of ruinous decay. The streets were overgrown with grass, and it was no uncommon sight to see cows and pigs grazing upon them. Outside stairs, street projections, ruinous walls, dunghills, pigsties, and other abominations everywhere met the eyes, while noxious effluvia everywhere saluted the nasal organs.”

HLP’s impact on St Andrews was recorded elsewhere, as follows: “During the period these changes were in progress, repeated grants were obtained from the Legislature for the rebuilding and improvement of the Colleges; making St Andrews, so far as educational privileges are concerned, second to no town in the kingdom. These improvements were nearly all carried out and conducted by the late Lieutenant Colonel Sir Hugh Lyon Playfair, LL.D., who, as provost of the city for many years, devoted himself to the renovation of the town so successfully, that it may be said he found it in ruins, and left it a city of palaces.” It is also recorded that he was instrumental in having the railway line extended to the town.

The Sketch continues: “Although ‘The Major’ had retired from active service as a soldier, it was only to

enter on active service as a citizen. Himself a keen golfer, and knowing how popular the game had been in India, he first of all set about improving the Links, which then lay almost an untrodden waste. A company of golfers had indeed existed since 1754 …. but little system was observed in promoting either the amusement of its members, or the facilities for playing the game. Up unto the year 1833 there was no Clubhouse for this association, till, through his exertions, rooms were rented for their occupation.” In fact, HLP formed the Union Club in 1835 with a membership which consisted almost exclusively of Royal and Ancient Golf Club members. The Union Club ran a small clubhouse facility called the Union Parlor and in 1853 built a new clubhouse behind the first tee of the Old Course. Completed in 1854, it continued to be known as the Union Clubhouse until both Clubs formally merged under the Royal and Ancient title in 1877.

HLP was the driving force behind the building of the R&A clubhouse. His golfing career was long and distinguished. Besides the honors noted above, he also won the R&A’s gold medal again in 1842, as well as the Scotscraig gold medal twice more and the North Berwick Golf Club’s Glensaddell gold medal in 1835 and 1841.

A vivid portrait of Playfair survives in Charles Lees’ The Golfers; A Grand Match of Golf St Andrews 1844. Major Playfair is playing in a two-ball foursome match and is about to sink a putt. The players are hemmed in by a crowd, many with betting books in hand: Playfair’s demeanor has been characterized:

That Major Playfair, man of nerve unshaken, He knows a thing or two, or I’m mistaken;

And when he’s press’d, can play a tearing game, He works for certainty and not for fame!

There’s none – I’ll back the assertion with a wager, Can play the heavy iron like the Major.

It is the author’s contention that, had it not been for this son of St Andrews, the game of golf might have gone into permanent decline in Scotland. Lt. Col. Sir Hugh Lyon Playfair honed his golfing skills in Bengal and brought his talents as administrator and man of action in the service of John Company to reverse the terminal decline of the game at St Andrews, the University and the town itself. The older Honorable Company of Edinburgh Golfers went into administration between 1831 and 1836, when it reformed at Musselburgh, before moving again, to Muirfield in 1891. It is possible that if the ‘upstart’ St Andrews Society of Golfers and its patron, the colonial Playfair had not kept the flame alive during the early part of the 19th century, the game of golf may well have continued its decline in popularity.

Playfair was a founding member of the first-ever photography association, the Edinburgh Calotype Club.

The Club is the oldest photographic club in the world and these collections of photographs arranged in two volumes – volume one is held at the National Library of Scotland; a second volume, which we have termed ‘volume two’ is held at Edinburgh Central Library. Apparently, there were no articles of association and no minutes were kept of meetings. By all accounts it was quite an informal, convivial affair:

‘The meetings were held periodically at the houses of the members alternately, and generally each took the form of a breakfast, although when some greater step than ordinary had been made in advance it was generally honored by being introduced to the members at a formal dinner’.

The names of the eight members of the Club have been traced and photographs by five members and a number of associates appear in the albums. They were professional men – advocates, doctors and academics in Edinburgh and in St. Andrews. The Club was in existence until probably the mid-1850s, when the albumen and collodion processes superseded the calotype. These new developments meant that ‘the practice of photography was no longer confined to the few, but spread like wildfire over the country.’

The names of the eight members of the Club have been traced and photographs by five members and a number of associates appear in the albums. They were professional men – advocates, doctors and academics in Edinburgh and in St. Andrews. The Club was in existence until probably the mid-1850s, when the albumen and collodion processes superseded the calotype. These new developments meant that ‘the practice of photography was no longer confined to the few, but spread like wildfire over the country.’

The Edinburgh Calotype Club had, in a sense, outlived its usefulness, though some of the members, especially Cosmo Innes and George Moir, became active in the Photographic Society of Scotland, founded in 1856.

The Edinburgh Calotype Club was able to flourish in Scotland during this time as the patent Talbot had taken out in England in 1841, to protect his invention, did not apply in Scotland. Although in general the quality of the work produced by the club does not come close to matching that of the photographic pioneers David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, it is interesting to contrast the work of the enthusiastic amateurs with that of more skilled practitioners. Indeed, there are close links between the club and their two more illustrious contemporaries: Robert Adamson was introduced to photography by his older brother John, a doctor and chemist in St. Andrews, two of whose photographs appear in volume one.

I found no images of golfers in these very earliest images, but there are several of Mr. Playfair and numerous images he personally took, mainly of buildings and church facades.

- Robert Birman